The Motor Launch Patrol by Gordon S. Maxwell

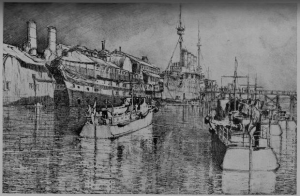

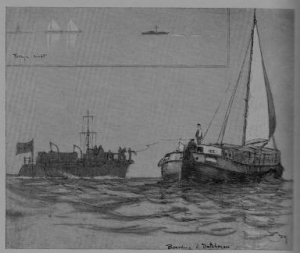

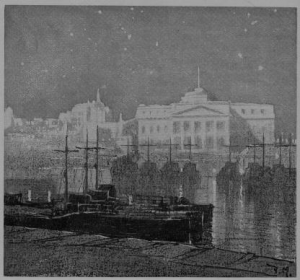

In The Motor Launch Patrol Gordon Maxwell, Lieut., RNVR recounts his life in the Motor Launch Patrol during WWI (commanding ML 314). He includes numerous humorous and horrifying anecdotes, provides insights into little details of life aboard, and generally pulls the reader into the daily life of an RNVR officer during the war. Maxwell's brother, famed artist Donald Maxwell (also a Lieut. in the RNVR in command of ML 139) provides a number of sketches and watercolours depicting the men and craft of the Motor Launch Patrol in action. Included here are some excerpts from his book along with a few images to give a feel for what life may have been like aboard these boats during the war.

The blurb on the dust jacket states: "This book tells the history of one of H.M. Motor Launches from commissioning to paying off; from the monotony of patrol life to the fierce excitement of the Zeebrugge Raid, as well as having much information about the MLs generally in home and foreign waters. It is full of vivid incident, both serious and humorous, and is a unique record of the patrol work of the RNVR in the War."

In The Motor Launch Patrol Gordon Maxwell, Lieut., RNVR recounts his life in the Motor Launch Patrol during WWI (commanding ML 314). He includes numerous humorous and horrifying anecdotes, provides insights into little details of life aboard, and generally pulls the reader into the daily life of an RNVR officer during the war. Maxwell's brother, famed artist Donald Maxwell (also a Lieut. in the RNVR in command of ML 139) provides a number of sketches and watercolours depicting the men and craft of the Motor Launch Patrol in action. Included here are some excerpts from his book along with a few images to give a feel for what life may have been like aboard these boats during the war.

The blurb on the dust jacket states: "This book tells the history of one of H.M. Motor Launches from commissioning to paying off; from the monotony of patrol life to the fierce excitement of the Zeebrugge Raid, as well as having much information about the MLs generally in home and foreign waters. It is full of vivid incident, both serious and humorous, and is a unique record of the patrol work of the RNVR in the War."

IV

ON PATROL

THE SERIOUS SIDE

THERE seems to be among some people an idea that life on patrol in the RNVR is a sort of glorified yachting holiday. The kind of people who think this are invariably those who know the least about it, and therefore, with the dogmatism of ignorance, say the most. I doubt if one of them could tell you offhand the difference between a binnacle and a barnacle, or a fairlead and a fairway; and they would have as much chance of success if they tried to box Carpentier as if they attempted to box the compass.

ON PATROL

THE SERIOUS SIDE

THERE seems to be among some people an idea that life on patrol in the RNVR is a sort of glorified yachting holiday. The kind of people who think this are invariably those who know the least about it, and therefore, with the dogmatism of ignorance, say the most. I doubt if one of them could tell you offhand the difference between a binnacle and a barnacle, or a fairlead and a fairway; and they would have as much chance of success if they tried to box Carpentier as if they attempted to box the compass.

Of course, on the other hand, there are a few dear simple souls who imagine that we spend our lives with submarines popping up all around us like a school of porpoises, and that all we have to do is merely to round them up something after the fashion of a sheep-dog tending his flock. It would be difficult to say which opinion is the more incorrect. Nor are these erroneous ideas always confined to gossip; they find their way into print quite frequently. I remember reading one delightfully humorous - unconsciously so, of course - article in a newspaper on the work of the motor launch patrol, crammed with impossibilities; but the gem of them all was the statement that MLs always went out on patrol about twenty at a time, accompanied by a "mother" ship, usually a cruiser! The latter, it went on to say, would remain in the centre of a seven-mile circle with the launches cruising round her, and (at the distance of seven miles) each ML kept in touch by flag signals with the "mother" ship the whole time! When it is considered that the size of the average ML flag is 32 inches by 23, it will be seen what eagle-eyed beings we are - though I think a man with such a range of vision is wasted on an M. L; the sort of job he ought to have would be as assistant to the Recording Angel, when he could sit on a cloud "hard by heaven" with a pair of binoeulars and a notebook, and watch the doings of mere mortals on the earth beneath.

For the benefit of those not acquainted with MLs, a few descriptive lines may not be out of place here of these little grey ships which patrolled out of almost every port in Great Britain and the Mediterranean. Eighty feet in length, with a twelve-foot beam, they are capable of a speed of over twenty knots, and carry two officers and eight men. Their shallow draught is a great asset, for not only does it render them more or less immune from a torpedo attack, but enables them to get to a certain point quickly by means of short-cuts which would be impossible for larger craft. For their size they are heavily armed; a gun is mounted forward, while aft are a couple of depth-charges, those unpleasant under-sea explosives, set for various depths, which make it very unhealthy for any submarine in the vicinity, even without a direct hit. Four smaller depth-charges are carried also. Then there are lance-bombs for close work, as well as the rifles and revolvers and a Lewis-gun.

Considering their size, the interior accommodation of these boats is very good; there is no waste space. Right aft are the officers' quarters, a sleeping cabin with two bunks, and a smaller cabin about as big as a fair-sized dining-table, which is dignified by the name of "ward-room." Next is the galley. The engine-room is amidships, with the chart-house just forward of it. The magazine comes after this, and this adjoins the fo'castle, where the crew sleep and have their being - rather a crowded being.

For the benefit of those not acquainted with MLs, a few descriptive lines may not be out of place here of these little grey ships which patrolled out of almost every port in Great Britain and the Mediterranean. Eighty feet in length, with a twelve-foot beam, they are capable of a speed of over twenty knots, and carry two officers and eight men. Their shallow draught is a great asset, for not only does it render them more or less immune from a torpedo attack, but enables them to get to a certain point quickly by means of short-cuts which would be impossible for larger craft. For their size they are heavily armed; a gun is mounted forward, while aft are a couple of depth-charges, those unpleasant under-sea explosives, set for various depths, which make it very unhealthy for any submarine in the vicinity, even without a direct hit. Four smaller depth-charges are carried also. Then there are lance-bombs for close work, as well as the rifles and revolvers and a Lewis-gun.

Considering their size, the interior accommodation of these boats is very good; there is no waste space. Right aft are the officers' quarters, a sleeping cabin with two bunks, and a smaller cabin about as big as a fair-sized dining-table, which is dignified by the name of "ward-room." Next is the galley. The engine-room is amidships, with the chart-house just forward of it. The magazine comes after this, and this adjoins the fo'castle, where the crew sleep and have their being - rather a crowded being.

The seaworthiness of these boats is better than many people imagine, and on the whole they are fairly easy to handle, though in a high following sea an ML is apt to sheer badly, or to "take the bit between its teeth" at times and side-slip down a big wave. That, perhaps, is their worst fault. Of course, there are days when the sea is too high for patrol, for commonsense has to be used in the organisation of the work; but if it is too rough for an ML to keep the sea, it is usually too bad for a submarine to operate also. But MLs can stand, and have stood, some terrible weather, and to call them fair-weather boats is not a libel, it is merely a stupid lie.

It would be hypocrisy to deny that certain days of patrol work in the few summer months are pleasant - they are, with the spice of danger and adventure to save them from becoming too monotonous, but I think we earn this by the rough times we have in the winter months. Writing, as I am, just after going through a long and hard winter in the North Sea, I can speak as one who knows, and a glimpse of an average twenty-four hours on patrol may be interesting.

In the grey of a bleak winter's morning three MLs set out from an east-coast harbour "line ahead" (it would be more picturesque to say "stole silently out of harbour," but an ML is never silent, unless drifting). Once clear of homewaters, the patrol leader runs up a signal to form line abreast; in this formation we proceed, with rails down and gun cleared away for instant action, depth-charges and lance-bombs set, and, if deemed necessary by the C.O., rifles and revolvers loaded; nothing is left to chance. There is a "certain liveliness in the North Sea" on this morning, quite a high sea is running, and soon the boat is feeling this, no boat sooner than an ML, and before long she is "shipping it green." Patrol may be a bit monotonous at times, but it can never be called dry work, anyhow in the winter. There are days when, however much you may wrap yourself up in oilskins, you will still get soaked, and your sea-boots act as involuntary foot-baths of ice-cold water. But this is a thing you have to grin (or curse) and bear on an ML on a rough day. Nor is the general wetness confined to the deck, as clothes, and boots testify if not worn for a few days, and a calm day is as bad as a rough one for this form of dampness.

It would be hypocrisy to deny that certain days of patrol work in the few summer months are pleasant - they are, with the spice of danger and adventure to save them from becoming too monotonous, but I think we earn this by the rough times we have in the winter months. Writing, as I am, just after going through a long and hard winter in the North Sea, I can speak as one who knows, and a glimpse of an average twenty-four hours on patrol may be interesting.

In the grey of a bleak winter's morning three MLs set out from an east-coast harbour "line ahead" (it would be more picturesque to say "stole silently out of harbour," but an ML is never silent, unless drifting). Once clear of homewaters, the patrol leader runs up a signal to form line abreast; in this formation we proceed, with rails down and gun cleared away for instant action, depth-charges and lance-bombs set, and, if deemed necessary by the C.O., rifles and revolvers loaded; nothing is left to chance. There is a "certain liveliness in the North Sea" on this morning, quite a high sea is running, and soon the boat is feeling this, no boat sooner than an ML, and before long she is "shipping it green." Patrol may be a bit monotonous at times, but it can never be called dry work, anyhow in the winter. There are days when, however much you may wrap yourself up in oilskins, you will still get soaked, and your sea-boots act as involuntary foot-baths of ice-cold water. But this is a thing you have to grin (or curse) and bear on an ML on a rough day. Nor is the general wetness confined to the deck, as clothes, and boots testify if not worn for a few days, and a calm day is as bad as a rough one for this form of dampness.

Towards midday the wind abates a little, but not so the cold, and oilskins give place to duffel coats - thick wool, yellowy-brown coats with hoods, and which, if worn with these up and baggy trousers of the same material, give the appearance of a ship manned by giant teddy-bears. Meals on an ML are "movable feasts," where the right hand never knows what the left hand may be doing, for while the latter is conveying food to the mouth the former is probably chasing the plate across the table or picking up a chop from the seat. No meal on patrol is ever dull. So the day wears on, varied by gun or rifle practice on certain days, and then begins by far the most nerve-racking part of patrol - the night work. Vigilance is always necessary, but this must be doubled during the hours of darkness. A look-out man must be stationed forward to warn the bridge of any object ahead, which may be a mine, a wreck, or a buoy, and recognition lights must be kept in readiness to be turned on in case of a challenge by another patrol boat. So, with engines running dead slow and every nerve alert, on through the blackness the ML prowls, with all lights extinguished save a couple or so in the engine-room, invisible from without, and the searchlight ready for instant use. Sometimes the engines are stopped, and we drift for an hour with the hydrophone out. This is an undersea telephone, and a man waits in the chart-house with the receivers to his ears for a submarine to ring up."

A submarine will not attack a patrol boat if it can help it, and it is often more useful to keep one of the former under the water, locating its position with the hydrophone if it moves, than to drive it away or engage it; for fresh boats can be brought up by a scout, and, as a submarine can only stay a certain time under and must come up to charge its batteries, its chance is small in these circumstances. This is known as "sitting on a submarine." Naturally they get away sometimes, for the sea is a wide place, but they are at least rendered harmless while in the vicinity of a war channel.

A periscope is a very difficult thing to see. Even when you know it is there it is none too easy; but not so a floating mine. Its size renders this fairly simple to locate, except, of course, at night, when you may be on it before the look-out man can give the alarm. Sinking mines by rifle fire is interesting and exciting work; a specially heavy rifle or a Lewis-gun are used, and the mines make splendid targets. If a mine is more than usually obstinate the gun is employed as well. It is not only floating mines that have to be accounted for, but also those washed ashore, which have to be towed off the beach into deep water before they are sunk. These are not all German, some being our own which have broken away from the numerous minefields owing to bad weather.

A submarine will not attack a patrol boat if it can help it, and it is often more useful to keep one of the former under the water, locating its position with the hydrophone if it moves, than to drive it away or engage it; for fresh boats can be brought up by a scout, and, as a submarine can only stay a certain time under and must come up to charge its batteries, its chance is small in these circumstances. This is known as "sitting on a submarine." Naturally they get away sometimes, for the sea is a wide place, but they are at least rendered harmless while in the vicinity of a war channel.

A periscope is a very difficult thing to see. Even when you know it is there it is none too easy; but not so a floating mine. Its size renders this fairly simple to locate, except, of course, at night, when you may be on it before the look-out man can give the alarm. Sinking mines by rifle fire is interesting and exciting work; a specially heavy rifle or a Lewis-gun are used, and the mines make splendid targets. If a mine is more than usually obstinate the gun is employed as well. It is not only floating mines that have to be accounted for, but also those washed ashore, which have to be towed off the beach into deep water before they are sunk. These are not all German, some being our own which have broken away from the numerous minefields owing to bad weather.

Thus night and day ceaseless, never-sleeping watch is kept round our coasts by these sea-wasps with their deadly stings, and when the history of the war is viewed down the perspective of time the public will realise better the strenuous, quiet, and effective work of RNVR men on these patrol boats.

The Motor Launch Patrol